Could Community Schools Help Fix Haiti’s Broken School System and Boost Rural Economy?

In Haiti, all children have the right to free quality education, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Historically, however, Haitian children have attended school only when their parents could pay for it. With the recent application of the Programme de Scolarisation Universelle Gratuite et Obligatoire (PSUGO), school attendance increased from 50 percent in 2005 to 83 percent in 2012 – a positive change, although the school system still faces significant challenges.

If children are now more likely to go to school, the quality is dismal. Only 15 percent of teachers are qualified to teach. Students enter school late – between the ages of 8 and 12 – with fairly high rates of being left back – 15 percent on average – increasing the rate of over-aged children in the schools (65 percent). The high rate of over-aged children in the schools undermines the system because it limits the number of seats available in schools, affects internal efficiency, discourages students and promotes school dropout. Indeed, more than half of Haitian children in primary school will not reach the 6th grade.

While these issues are pervasive in the country as a whole, they are a lot more pronounced in rural compared to urban areas. The result of such profound marginalization of rural families and their children has often been the abandonment of the countryside and agriculture for over-populated slums in urban areas to eek-out a living. Often, these children end up in domesticity or living on the streets, perpetuating an endless cycle of poverty and social inequity. This robs Haiti of a huge potential resource that must be recaptured if the country is going to develop.

In academic year 2013-2014, school officials implemented an accelerated program for the oldest over-aged children so they finish the first six years cycle in three years. However, over 90 percent of participants in the program either did not attend or failed the mandatory state exam to complete 6th grade. According to Mr. Pierre Jolivert, a seasoned teacher and District Inspector who oversees a large rural district in the South department, the students’ lack of confidence in their readiness was the primary reason for not showing-up or for failing the exam. This is not surprising given that the school curriculum was reportedly not well-adapted for this program and that teachers and principals were not properly trained. Skipping the mandatory state exam is also the crowning act of a disengagement process likely fueled by students being left back and by other social and economic inequities including hunger and malnutrition. Further, students who drop out often cite a lack of support as one of the primary reasons. Most children in the program had parents who did not have the skills to support them academically. In addition, when asked about their expectations regarding their education, over 60 percent of them (90 percent of over-aged students in domesticity) would prefer to learn a trade while also staying in school. The accelerated program failed to address these facts.

If measures to redress these problems are to be successful and sustainable, it is critical that they be evidence-based and adapted for the population and the environment. They must address not only the quality of the education these children receive in the classroom but also eliminate school fees, provide strong academic support and other health and social services including nutrition as well as vocational training. In fact, given the largely rural/agricultural background of this population, this could be an opportunity to expose them to and stimulate and nurture their interest in modern agriculture and train them when appropriate to be members of Haiti’s next generation of farming professionals.

The fact is, Haiti currently imports more than 50 percent of its food. Since the country is very young demographically – almost70 percent of Haitians are under age 30 – the population is expected to double by 2073. It is therefore imperative that Haiti creates the systems and trains the professionals that can help insure the country’s future food security. This could also encourage young men and women to remain in their communities and help build a vibrant rural economy that could relieve the pressure on cities with little capacity to absorb more migration.

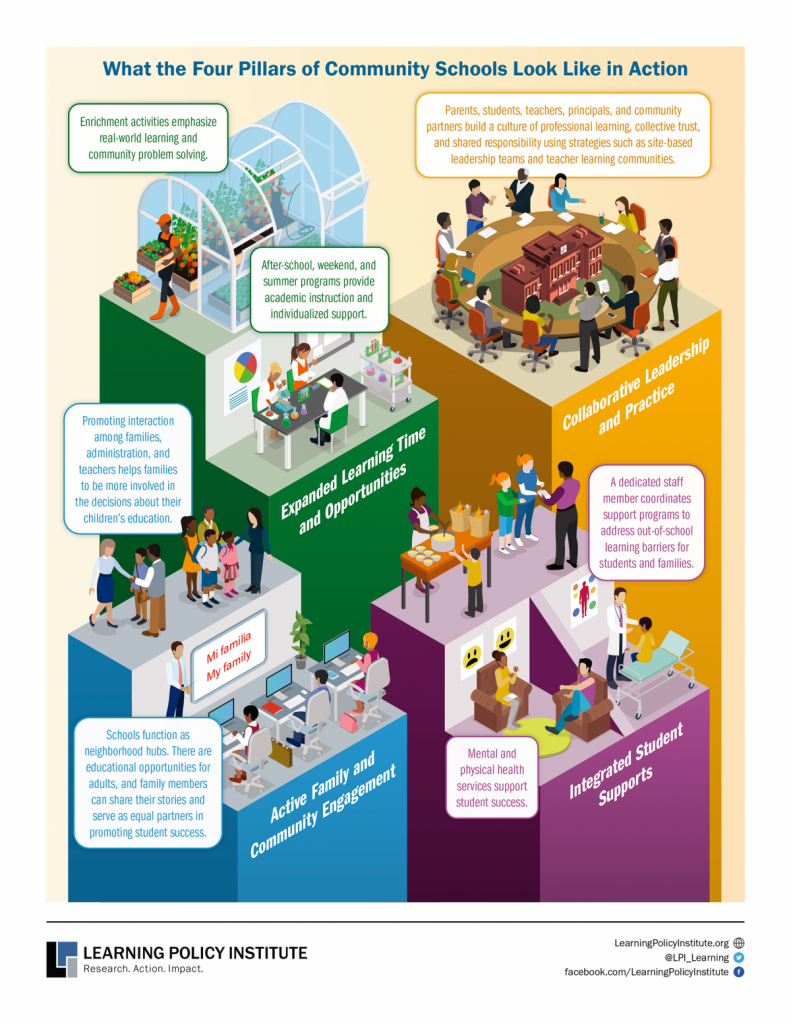

There is growing evidence that “ecoles amies des enfants” or “community schools” in the United States used successfully around the world and recommended by UNICEF could help redress Haiti’s fundamental schools and put children on the road to success, ready to contribute to the development of the country. “Community Schools are a place-based school improvement strategy in which schools partner with community agencies and local government to provide an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development and community engagement. Although the approach is appropriate for students of all backgrounds, many community schools serve populations where poverty creates barriers to learning, and where families have few resources to supplement what typical schools provide”. They bring partners with resources to the schools to help improve student and adult learning. They also have robust parental involvement that strengthens families and promote healthy communities. When well-implemented, community schools lead to improvement in student and school outcomes and contribute to meeting the educational needs of low-achieving students in high-poverty schools. They can also improve other outcomes such as behavior and absenteeism.

Aspects of the Community School Model are currently being tried in the rural district that Mr. Jolivert oversees in two schools that cater primarily to the poorest children. One public school, the Ecole Nationale Mixte de Camp-Perrin (ENM), has piloted a growing parents’ association to provide support for its students. The second school, Ecole Pere Gerard, which is administered by Oblates Missionaries in Mazenod caters primarily to children in domesticity. It has put a small agricultural farm in place where students are introduced to local food production.

Both schools are quite successful. According to Mr. Jolivert, all teachers at ENM are well-trained and state-certified, a rarity in a system where only 15 percent of teachers are qualified to teach. Students’ test scores are very high at both schools. Between 80-100 percent of their students have succeeded at official state exams consistently, this, even though ENM is housed in an unfinished overcrowded cinderblock building with no electricity or running water and poorly suited for teaching. While both schools are successful, over 90 percent of over-aged children attending the 2013-2014 accelerated program in these two schools also failed/did not show-up for their exams.

Given the academic strength of the schools, there is an opportunity to expand on the small pilots they are conducting to test and adapt the key features of Community Schools that are relevant to the reality of the over-aged children including strong academic support during and after school with apprenticeships and mentorship programs, health and nutrition/feeding programs and the vocational training that so many of the oldest over-aged children asked for and provide the knowledge and skills they need for the labor market. The schools should also provide entrepreneurial and technical skills so students could learn to create jobs for themselves. In addition, efforts should be made to improve the infrastructure at ENM including the building, clean running water and electricity.

The school farm pilot should not only train children for farming sector jobs when appropriate but also stimulate and nurture the interest of the general student population in the sector. Because they witness the economic struggles of their parents as farmers with little modern tools or technology, rural youth face particular barriers that often lead to skepticism about farming as a business and economic enterprise with a viable future. A similar program to provide updated agricultural training to students’ parents to help improve their skills could also be tested. The school could look for partnerships with agricultural programs at local colleges to help educate children about all aspects of agriculture, including technology. The program should help young people see farmers as innovators playing a central role in feeding their country and not just as producers who are making ends meet. The school farm should be a garden classroom fully integrated into the academic experience, the nutrition/feeding program and the culture of the school where students learn how to produce and prepare food and appreciate its impact on their health, communities and the environment. If successful, this model could be scaled to other local schools and later, to other rural districts.

Community Schools have the potential to revolutionize fundamental education by vastly improving the academic success of the most marginalized in Haiti’s school system. Also, agricultural education and training for children/parents could give them a new vision of farming. It could create an environment that allows producers to thrive, allowing Haiti to make progress towards ending hunger. Finally, it could decrease the growing pressure on urban areas by giving rural youth a viable reason to remain in their communities and help build a vibrant economy.

Sandra Jean-Louis, MPA

Ms. Jean-Louis graduated from New York University (NYU) Wagner School with a master’s degree in Policy and Management. With over 20 years of professional experience, she facilitates impact collaboration in the areas of health equity and food security between communities, government, and the private sector.

[email protected]

notwithstanding